In 18th-century Edo Japan, the study of the Chinese classics was advocated by the Tokugawa shogunate and led to renewed interest in late Ming literary culture. One result was the development of the bunjin, gentleman-scholar, after the Chinese wenren. While the bunjin had to be well versed in the Chinese classics, calligraphy and poetry, painting was considered one of his accomplishments. The literati school of painting, bunjin-ga, also known as nan-ga, ‘southern school’ of Chinese extraction, had a significant following. This retrospective exhibition at the Miho explores the artistic creations and life of the artist Yosa Buson (1716-1784).

Its spontaneous brushwork and freedom of expression approached with high poetic content, found favour in the then kamigata area (present-day Kyoto-Osaka region), one of the first receptive to new artistic trends. Half a century earlier, the transition in the 1640s from Ming to Qing China had witnessed a considerable number of disaffected Chinese artisans leaving for Japan. Their entry was facilitated by the opening at the same time – during the Kan’ei era (1624-43) – of the port of Nagasaki to the outside world. Although their influence was limited, some minor Chinese artists managed to slip into the country, including one Shen Nanpin around whom a school in Nagasaki formed.

The opening decades of the 18th century saw some highly individualistic painters call the former capital, Kyoto, home. They included Ito Jakuchu (1713-1800), an avid naturalist, Ike no Taiga (1723-76), noted for unconventional brushwork and Maruyama Okyo (1733-95), known for realism. One bunjin drawn to the poetic tradition was Yosa Buson.

Early Life of Yosa Buson

Yosa Buson began life as a poet, was a monk and a master of haiku poems in the seventeen-syllable style long before he embarked on a career as a painter. Leading a peripatetic existence before settling in Kyoto, he was identified with the haiga, a genre incorporating the haiku poem and painting, which he perfected into an art form. Conversant too with the haikai, comic verses, he injected a sense of humour from his brush. He then studied the classical styles of the Chinese masters, and inscribed his literati painting with poetry as was fashionable. Experimenting with manifold styles, his work had eclecticism, yet it remained quintessentially Japanese.

Largely self-taught, and considering he only started painting around the age of 40, Buson had a prolific repertoire. He is the subject of Yosa Buson: On the Wings of Art, a major retrospective devoted to him at the Miho Museum, Shigaraki in Japan. Much emphasis is placed on the influence of poetry, the basis of Buson’s talent, in the 150 objects displayed.

The Poetry of Yosa Buson

They include one National Treasure and 18 Important Cultural Properties, of which 11 belong to the Agency of Cultural Affairs in Tokyo. Navigating his special contribution to the fine and decorative art of Edo Japan are handscrolls, hanging scrolls, fusuma-e, painted sliding panels and byobu, folding screens, gathered from public and private holdings throughout the country. They reflect Buson’s immense range and address his aesthetic sensibilities. He had a rare understanding of form and exploited its boundaries to create anew. A picture of the man and his art is supported by an exchange of rare letters that Buson enjoyed with like-minded haiku compatriots 250 years ago.

Born in Settsu province, present-day Osaka area, Yosa Buson left for Edo, the seat of the shogunate, as a young man to study poetry under Hayano Hajin. At the time there was a revival of the haiku style associated with Matsuo Basho (1644-94), the greatest of Japan’s haiku poets who elevated the form to near perfection. Basho’s seminal work, Oku no hosomichi, ‘The Narrow Road to the Deep North’, a travel memoir, deeply moved Buson and forms the opening and dominant theme of the exhibition.

The Screen The Narrow Road to the Deep North

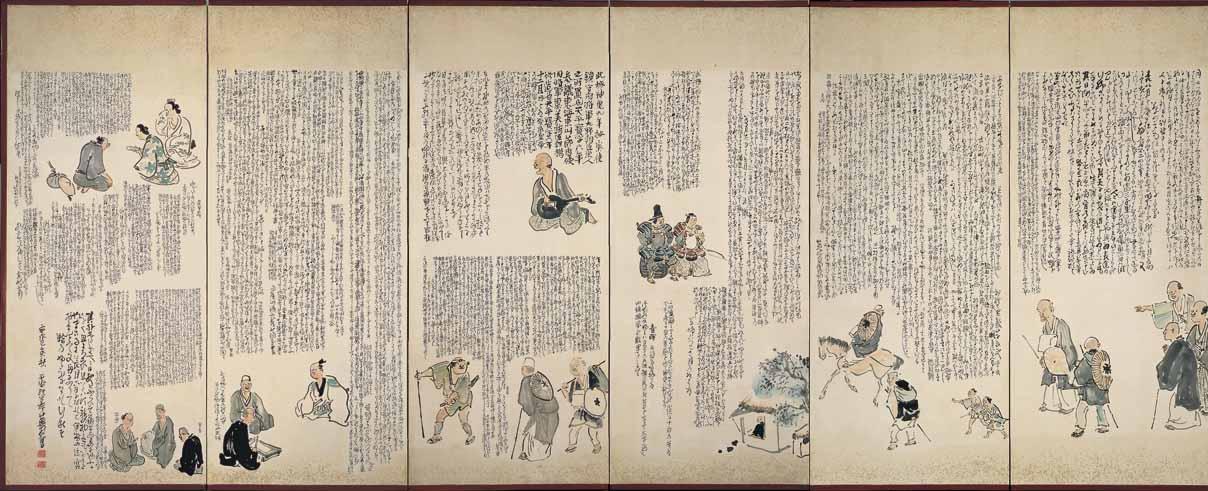

Often called Basho’s heir apparent, Buson employed a startling originality when he interpreted the master’s work. Whether in poetry or on painting, he explored new avenues to make the latter’s inimitable style known. In the autumn of 1779, Buson depicted ‘The Narrow Road to the Deep North’ pictorially on a six-panel screen. No greater tribute to Basho has been rendered by his disciples or by anyone else, an expression of Confucian deference between pupil and teacher.

It is the only extant screen of the original poetry text in its entirety. Accompanied by nine illustrated episodes, their placement suggests the momentum of early yamato-e or Japanese-style narrative painting. Spatially interspersed amid text are figural depictions such as a hermit, a bride and courtesans and various background settings, the intention being to make the work reach as wide an audience as possible.

The memoir also inspired Yosa Buson to embark on his own wanderings to the ‘deep north’. After his teacher Hajin’s death, he decided in his late twenties to visit fellow disciples. A year later, he assumed the name ‘Buson’ inscribing it on his poetry. Living first in Yuki in Shimousa, presentday Ibaraki prefecture, Buson then became a Jodo sect monk, travelling around Japan. Returning south in 1751, his stint at Miyazu temple, northern Kyoto was much cherished. The whimsical haiga handscroll, Sannhaisouzu, ‘Three Priests’, was made in memory of the monks, Ryoha, Roju and Chikukei, who shared his love of the haiku, by using their haiku pen names.

Return to Kyoto

It is not known why Yosa Buson returned to Kyoto in 1757 and renounced his calling. Whatever, his resolution to devote himself wholeheartedly to the haiku and to seriously paint enriched the Kyoto artistic community. Within a decade Buson emerged a central figure in the local Sankasha haiku group. His friendships with fellow haiku poets, are also celebrated in the exhibition.

Among them was Kato Kyotai (1732-92) of Nagoya, whose anthology, Aki no hi, ‘Autumn Days’, influenced the revival of Basho-style poetry in 18th-century Japan. As was the custom, Kato inscribed a haiku as a gesture of friendship on Buson’s Wasurebana, ‘An Old Man’, (1778), a figural allegory on ‘flowers blooming past their season’. Buson’s bond with the poet, Tan Taigi (d. 1771), who taught him spontaneity in verse, is evident in the haiga, Taigi and Buson in a Storm, (1777), a sketch to celebrate their camaraderie on the seventh anniversary of Taigi’s demise. The latter is clinging onto a brolly blown inside out, with one clog flung asunder, while Buson clutches his half-closed one, both weathering the elements.

Yosa Buson and Haiku

If Yosa Buson’s work had an intrinsic purity, it was culled from the haiku. Although deceptively simple, one haiga, Mount Fuji and Pines, an Important Cultural Property, quietly states the elements as having a profound impact of Buson’s work: ‘How luxuriant the spring foliage everywhere, leaving only Mount Fuji uncovered’. The snow-covered mountain juxtaposed against pines in the foreground, has a lighter sky on the left, indicating rain has abated. On the right passing showers leave a darker horizon.

The theme of passing rain was often employed by Buson also in haiku form. Shigure, ‘Winter Rain’, lamenting the harshness of the first winter rains, is in fact an allegory on the winter of life. The spirit of the haiku enabled Buson to find a simple resource in native folk events. A fan painting, Bon Odori Dancers, enacts the Bon dance originating from Buddhist ritual with three dancing figures, as opposed to the usual procession form. Moving gestures, suggesting rhythm, are communicated by speedy brushstrokes of the three, one holding a fan. A cryptic meaning is provided by two haiku verses inscribed: ‘Dancing around the nishikigi (brocade tree)’ is a play on courtship suggested by dance and ‘Four or five dance as the moon descends’ enacts the end of the Bon Odori when few dancers are left as dawn approaches.

Studied Chinese Literati Painting

In the interim, Yosa Buson studied Chinese literati painting from technical manuals brought by painter Shen Nanpin, who visited Japan in 1731 and 1733. Abiding by the rules in the classical tradition, he learnt landscape painting techniques by copying the works of Ming masters, among them Shen Zhou and Wen Zhengming. His talent was soon evident and the local byobu ko, folding screen association, commissioned him to create works from 1763 onwards. There were ready clients among the many temples and shrines dotting the former capital.

However, Buson’s talent spread much further. From the deep north, the Gugyoji temple in Ibaraki is offering Plum Blossom, a fusuma-e of four panels, in its possession. Here the versatility of Buson’s brush is made known. His delicate rendering of the blossom’s slender branches contrasts with coarse dry strokes for the trunk.

By 1768, Buson had established a professional reputation. He was featured in that year’s edition of the Heian Jimbutsushi, a ‘Who’s Who’ of Heian-kyo or Kyoto artists with biographical references. An important commission that followed was a major collaboration with Ike no Taiga, one of Kyoto’s eminent artist ‘trio’. Together they worked on a landscape entitled Juben jugi, ‘Ten Conveniences and Ten Pleasures’, (1771).

Buson’s album, Jugi-cho, ‘Ten Pleasures’, a National Treasure, is on special display. As was the norm among bunjin, Yosa Buson had several literary names. Upon settling in Kyoto, he used ‘Yosa’, probably after his mother’s birthplace in Tango province. Another signature, ‘Sha’in’, was possibly from an ideogram of his childhood name. After 1770 he employed the colophon, Heian Yahantei Buson sha, ‘Yahantei Buson of Kyoto’, when he inherited his teacher’s mantle of haiku master and his Yahantei studio.

Yosa Buson’s Love of Poetry

Buson’s love of poetry extended to China. The Tang poets, Wang Wei and Li Bai exerted a profound influence on his painting, leading him to incorporate a humanity in his portrayal of figures. Nocturnal compositions such as the stillness of the Kyoto night also appealed to him. One handscroll, Spring Night Banquet among Peach and Damson Blossoms, (1781), was made in honour of Li Bai using the night theme. Five scholarly figures sit under blossoms, enjoying their beauty, a figure holding a brush perhaps the poet himself.

Yosa Buson’s hallmark was his treatment of figures, composed with animated expression in colour. Accompanying them is a 120 ideogram-text widely admired as a sample of the finest literary prose from the Kobun shinpo koshu, ‘True Treasury of Ancient Styles’, (Guwen zhenbao houji). Its opening lines are memorable: ‘Heaven and earth are but temporary abodes of all things, Days and nights are but travellers through one hundred generations, Thus is life but a dream’. The phrase also appears in ‘The Narrow Road to the Deep North’, as Buson’s deference to Basho was never far away.

Symbolic allusions to the ‘Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove’ are found in a hanging scroll, Tea Tasting under the Pines, (c.1760s?). Two scholars sip tea while a third is standing under prominent pines in colourful detail. The pine is a symbol of enduring friendship, suggested by its resilience to extreme climatic changes. The three figures are rendered in quiet humour, a tribute to friendship.

Painting is Poetry Without Sound

The Chinese adage, ‘painting is poetry without sound’ was something Buson naturally understood. His landscapes may seem Chinese in inspiration but they were Japanese in mood. One wistful composition, A Cottage in Winter, (1778), is a monochromatic hanging scroll of deft brushwork. The starkness of bare trees in a snow-covered grove suggests the spirit of wabi, rustic austerity after the Japanese manner.

Adapting literati principles on different mediums, Buson created new devices, which were his own. Perhaps his finest accomplishment is a previously unknown masterpiece, Landscape, (1782), an idealised monochrome composition on a pair of silver byobu, six-fold screens. Along a stretch of water, a hidden path joins the two screens, winding through wrinkled mountain ridges on the right to reach a rolling slope on the left. The landscape encapsulates the literati principle, evoking a ‘reclusive Utopia that dwells in one’s breast’, inspired by Chinese poetry.

Yosa Buson completes it by inscribing a Yuan (1279-1368) poem by Yu Ji from the Lianzhushige, an anthology of selected works. The landscape apart, the screens have been designed to convey the ephemeral quality of light. Eschewing gold leaf treatment of Momoyama (1573-1603) taste, Buson applied the subtlety of silver leaf squares. His genius was to create a rare vision of nature through poetry. It came to its full flowering when it was captured in painting, on surfaces and forms that only he understood.

BY YVONNE TAN

Yosa Buson: On the Wings of Art is at the Miho Museum, 300 Momodani, Shigaraki, Shiga 529-1814, Japan, until 8 June. www.miho.jp